THE GINGERBREAD METHOD — PATRICK WILLIAMS

/Comrades, the school should have a special baker if children are to eat the alphabet. Picture a long list of gingerbread words arranged according to length. The child gnaws letters from left to right, learning to read. The first old-time reading primers included this method. But even early on, boys and girls were driving away teachers by spelling out troublesome little dough rhymes about American history like “John Adams did die and so must I” and “While patriots do paraphrase, torture is largely commonplace.” In modern teaching practice, reformers have discarded these methods as trash; most of the gingerbread books were scathingly denounced. Nowadays, for example, Ruth texts Timothy harmonious moral lessons of childhood street genius. Then he marks the texts read and may return them later, perhaps with pictures of things. And thus the pupils are taught to read in glimpses of narrative, in a variety of forms, all while handling different styles of mechanical objects. One cannot protest: the child soul revels in crude play. For millions of present-day users, however, the combination of multiple devices and thinking in scraps of thoughts results in extreme confusion.

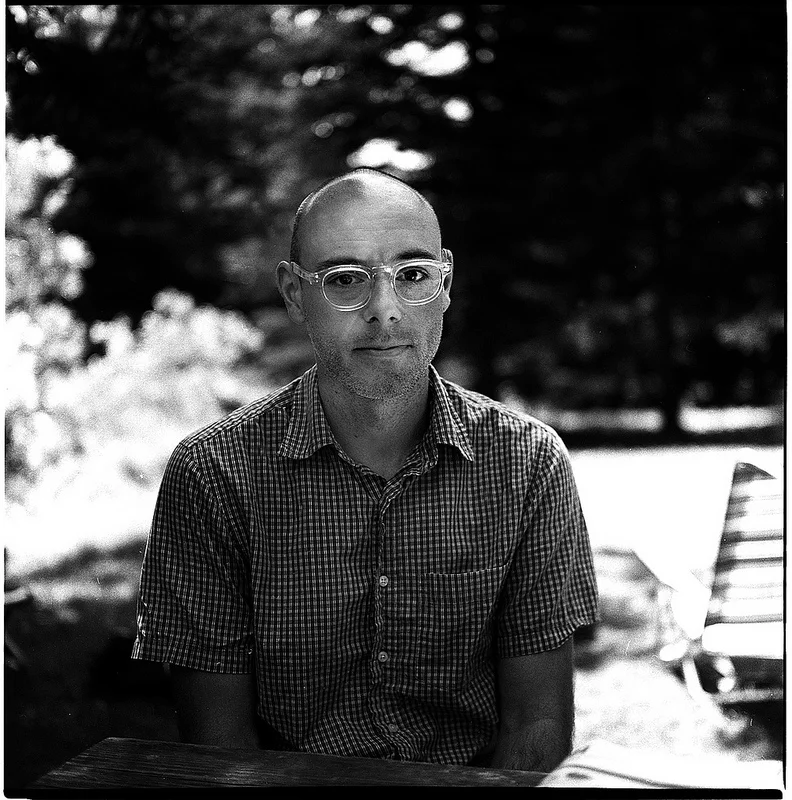

Patrick Williams is a poet and academic librarian living in Central New York. His work has appeared in publications including The Metric, Word Riot, 3:AM Magazine, M58, The Collapsar, Hot Metal Bridge, and elsewhere. He is the editor of Really System, a journal of poetry and extensible poetics.