CHIN UP — SARAH LAYDEN

/My interior is made of dark red. I have seen inside my body thanks to a tiny camera. I have watched the dark spots burn away at the hands of a doctor with a tiny iron, the smoke rising from the warm dark wet space of me, a pair of cotton hands staunching the blood. I hear the word cauterize. The word lesion. The word adhere. I want to turn my head away. I want to watch, to look, to bear witness. It is difficult to conceive of inner beauty while watching the video of one’s own laparoscopic surgery.

The disease hid itself, impossible to detect save for symptoms in retrospect. Certain failures. Pain I grew to think of as normal, pain that grew by degree and amplitude and with magnified dread, but remembered always in that regrettable Midwestern way, Chin up, tough it out, it doesn’t hurt that bad.

Pain-by-numbers. Doubled over by Cycle Day Four. One T-shirt of fifty percent cotton made three times heavier from sweat. I composed theories of relativity that it could be a hundred times worse. Believable because I’d been told as much. Sometimes, believing others’ lies is better than believing pain.

After the camera was turned off and the instruments cleaned, after I woke up, the nurse with the morphine asked me if the pain was a five or a ten. A voice came out of me saying, It’s not that bad. And then I tried to sit up. Seven, I said, and she pushed the button and I eased back.

I didn’t tell anyone because – how could I tell? How could I know that this thing inside me was not normal, not in the way everyone complained about, that mine was a special secret pain personalized to me? Who would listen? Chin up, chin up. We are alone until another person enters the room. Sometimes even then.

Listen: once I climbed a tree in a pale lavender sundress, my knees scarred with permanent scabs, and the oak bark flecked onto the smock in a way I knew my mother would not abide, but to me it was a pattern that added beauty, purpose, gave me a new way of looking at an old thing. But gazing down turns you blurry, eyes crossed painfully, until you see nothing. In those branches, all it took was me lifting my chin: I could see the roof of my house, and the way twigs caught in the gutter like little spring nests. Maybe they were nests. All that had been there before, too, without me knowing, without me seeing. First I had to look to make a thing real.

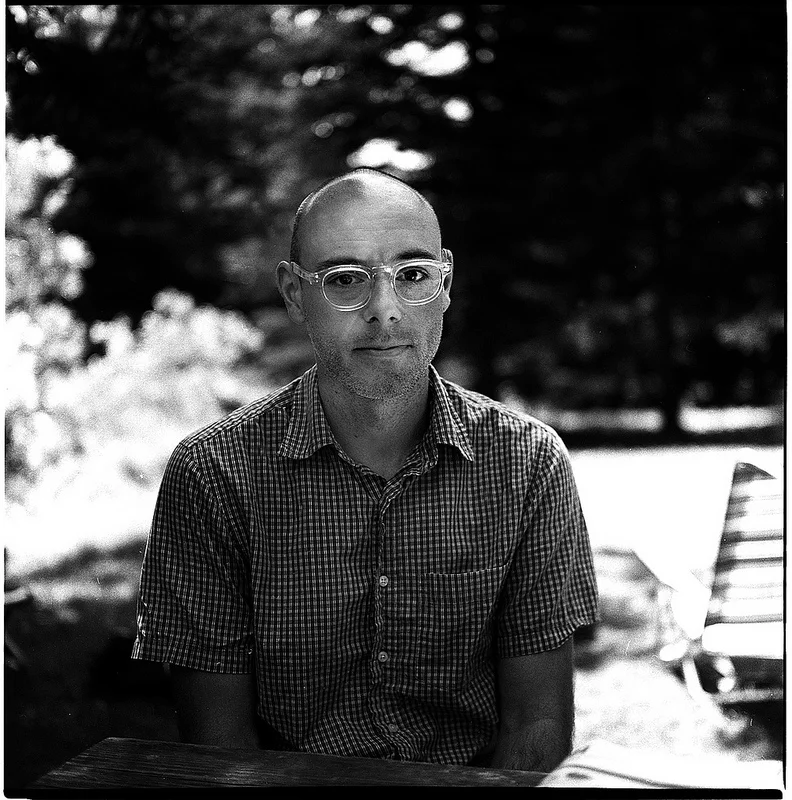

Sarah Layden's debut novel, Trip Through Your Wires, is forthcoming from Engine Books. A graduate of Purdue University's MFA program, her fiction, poetry, and essays have appeared in Stone Canoe, Blackbird, Artful Dodge, Reed Magazine, [PANK], Ladies' Home Journal, The Humanist, and elsewhere. She is a lecturer in the Writing Program at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.